One of the acknowledged challenges of Lockdown 2.0 has been finding ways to use spare time productively during the winter months. There is only so much DIY one can do, only so many household items one can justify improving, i.e. examining, breaking then fixing.

This month past my attention turned to a box that I have carted around with me for years. It’s a box that I have often looked at and speculated how much smarter I would become if only I found the time to open it and to analyse its contents. The box contains scoresheets of virtually every chess game I have ever played since I was ten years old. Stacking the scoresheets into separate bundles organized by opening scheme is a form of meditation in itself. Sicilians go here. Pircs there. Queens Gambits…make a new pile. Scanning the names of my opponents on each scoresheet has been a sobering affair. While I can visualise some adversaries as clear as day, other names conjure no face or figure to remind me of the hours we spent battling each other across the chessboard. The only proof of my opponent’s existence, their signature at the bottom of the scoresheet, the necessary imprimatur to confirm the result. There is a theory that you can only remember so many names or faces at any one time in life and that lapses in memory when it comes to the names of acquaintances you haven’t seen in a while are not only inevitable but normal. As we accumulate new contacts, they replace others we have lost touch with. Whatever about this theory, while sorting through scoresheet after scoresheet it became clear that there were some players I had played multiple times whom I couldn’t visualise and others whom I had only played once, whose faces were etched in my memory. I wondered what the criteria was for the games or opponents I could remember. Some were critical wins. Others hard-fought draw where I managed to cling on against the odds. Then there were those painful losses where I had blown promising positions against grandmasters or come a cropper in the last round of a tournament. Very occasionally, I would come across a scoresheet that was capable of transporting me right back to the moment in time when the game took place.

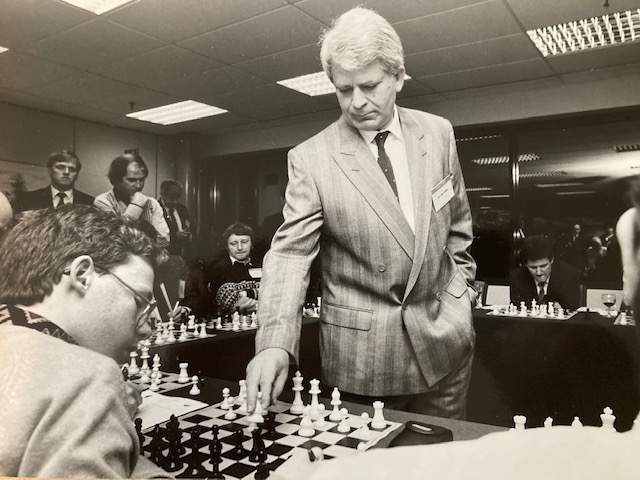

One such game was an encounter I had with the former World Champion Boris Spassky in a Simultaneous Display in Dublin in 1991 when I was fifteen-years-old. Spassky had lost the world title to my childhood hero Bobby Fischer in their infamous ‘Match of the Twentieth Century’ in Iceland in 1972. Soon after, Fischer abandoned his title and vanished from sight. When Spassky visited Ireland back in 1991, the mystery regarding Fischer’s whereabouts and whether he would return to chess to retake the world title represented my first major obsession. Perhaps, this is why my game with Spassky represents such a strong and enduring memory. For Spassky was the last man to play my childhood hero. The following year in 1992, after nineteen years away from chess, Fischer would return to the world stage and take on Spassky in a rematch in Yugoslavia. Sadly, there would be no great comeback for Fischer, however. No more displays of his remarkable chess genius – his rematch with Spassky more of a last stand against the world than a coda to the brilliant career that it should have been. Fischer’s example had inspired me to dedicate myself to chess and, on some level, he would always remain a personal hero. Playing Spassky and observing how at home he was with the world and within himself later helped me to gain some objectivity regarding Fischer. I came to realise that there comes a point when you should expect no more of personal heroes. If they’ve managed to inspire you, they’ve already given you everything they’ve got to give. So roll with it. And let them go.

Click on the link below to see an in-depth analysis of the game.

Sicilian-Move-order-Magic-Spassky-vs-Quinn-Dublin-Simultaneous-1991.pdf

SICILIAN MOVE-ORDER MAGIC SPASSKY VS QUINN DUBLIN SIMULTANEOUS 1991

For anyone interested in reading more about the background to Spassky’s historic visit to Ireland, the late John Bradley wrote an entertaining piece on how Jack Lowry came up with the idea of inviting Spassky to Kilkenny and how the Kilkenny Chess Club members mobilised to turn that dream into a reality. The article gives a wonderful insight not just into Spassky the man but it also gives a sense of the playful and jovial atmosphere that was, and remains, the essence of Kilkenny Chess Club, something which makes the club’s annual tournament each November one of the most popular weekender tournaments for professional and amateur players alike.

See https://www.icu.ie/articles/434